How to Discover Percentage Earth That I Visited

The last unmapped places on Earth

Have we mapped the whole planet? As Rachel Nuwer discovers, there are mysterious, poorly charted places everywhere, but not for the reasons you might think.

I

In 1504, an anonymous mapmaker – most likely an Italian – carved a meticulous depiction of the known world into two halves of conjoined ostrich eggs. The grapefruit-sized globe included recent breaking discoveries of mysterious distant lands, including Japan, Brazil and the Arabic peninsula. But blanks remained. In a patch of ocean near Southeast Asia, that long-forgotten mapmaker carefully etched the Latin phrase Hic Sunt Dracones – "Here are the dragons."

Today it is safe to say there are no unknown territories with dragons. However, it's not quite true to say that every corner of the planet is charted. We may seem to have a map for everywhere, but that doesn't mean they are complete, accurate or even trustworthy.

For starters, all maps are biased toward their creator's subjective view of the world. As Lewis Carroll famously pointed out, a perfectly objective and faithful 1:1 representation of the world would literally have to be the same size as the place it depicted. Therefore, mapmakers must make sensible design decisions in order to compress the physical world into a much smaller, flatter depiction. Those decisions inevitably introduce personal biases, however, such as our tendency to place ourselves at the centre of the world. "We always want to put ourselves on the map," says Jerry Brotton, a professor of renaissance studies at Queen Mary University London, and author of A History of the World in 12 Maps. "Maps address an existential question as much as one that's about orientation and coordinates.

"We want to find ourselves on the map, but at the same time, we are also outside of the map, rising above the world and looking down as if we were god," he continues. "It's a transcendental experience."

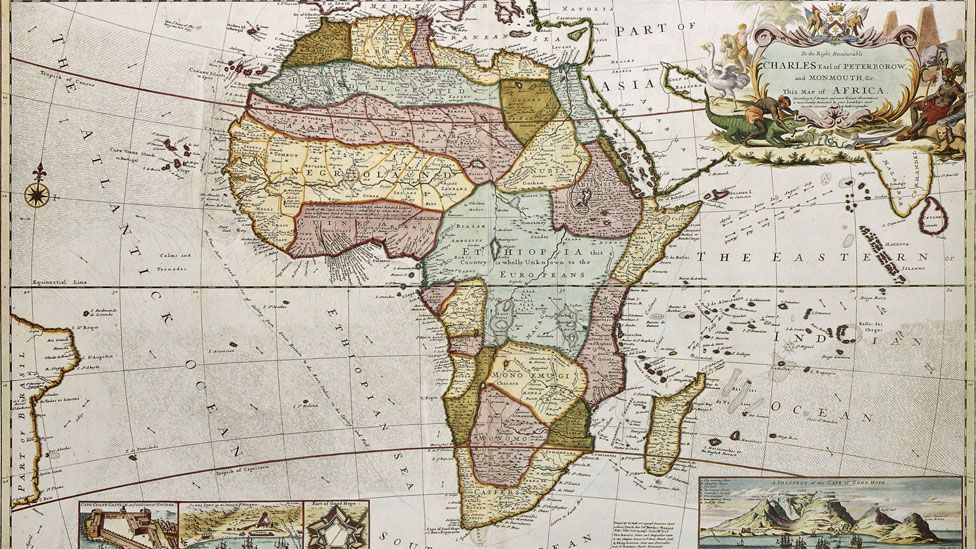

How Africa was seen in the 1700s (Thinkstock)

Which is why, he says, the first thing most new Google Earth users do is to look up their own address. Modern technology enables this exercise in ego, but the tendency itself is nothing new. It dates back to the oldest known world map, a 2,500-year-old cuneiform tablet discovered near Baghdad that puts Babylon at its centre. Mapmakers throughout history adopted a similar bias toward their own homeland, and little seems to have changed since then. Today, American maps still tend to centre on America; Japanese maps on Japan; and Chinese ones on China. Some Australian maps are even rotated so that the southern hemisphere is on top. It's such an ego-centric approach that the United Nations sought to avoid it when they created their emblem – a map of the world neutrally centered on the North Pole.

Similarly, maps can overestimate their creators' geographic worth, or reveal bias against certain places. Africa's true size, for example, has been chronically downplayed throughout the history of mapmaking, and even now, non-Africans tend to underestimate the size of that truly massive continent – which is large enough to cover China, the US and much of Europe.

Religious, political and economic agendas also come into play, adulterating a map's objectivity. The maps of World War II, for example, were incredibly propagandist, depicting "dreadful red bears and red perils," Brotton says. "The maps were distorted to tell a political message.

"A map," he continues, "will always have an agenda, an argument, a proposal about what the world looks like from a particular perspective."

Skewed view

Even today's digital maps adhere to this rule, he says. Google and other digital mapmakers turn the world into "one enormous web browser", he explains, driven by commercial interests.

But Manik Gupta, the group product manager at Google Maps, counters that Google Maps' primary goal mirrors that of its company: to organise the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful. Commerce is just one part of that. "At the end of the day, technology is a tool," Gupta says. "Our job is to make sure it's super accurate and works. Users then decide how they want to use it."

Nevertheless, even digital maps skew toward the things that their users deem most important. Those areas that the majority sees as unworthy of attention – poor neighbourhoods like the Orangi shanty town in Karachi, Pakistan, or the Neza-Chalco-Itza slum in Mexico city – as well as those places that mapmakers do not often go – war-torn regions, North Korea – remain grossly undermapped.

This neglect means maps of remote regions can contain errors that go unnoticed for years. Scientists paying a visit to Sandy Island, a speck of land in the Coral Sea near New Caledonia, recently discovered that the island simply did not exist. The "phantom island" had found its way onto Australian maps and Google Earth at least a decade ago, probably due to human error.

Google has two approaches to addressing these problems: sending mapmakers out into the wilderness with Street View cameras attached to backpacks, bikes, boats or snowmobiles, and launching Map Maker, a tool created in 2008 that allows anyone anywhere to enhance existing Google maps. "If it's important, then most likely the users will put it on the map," Gupta says.

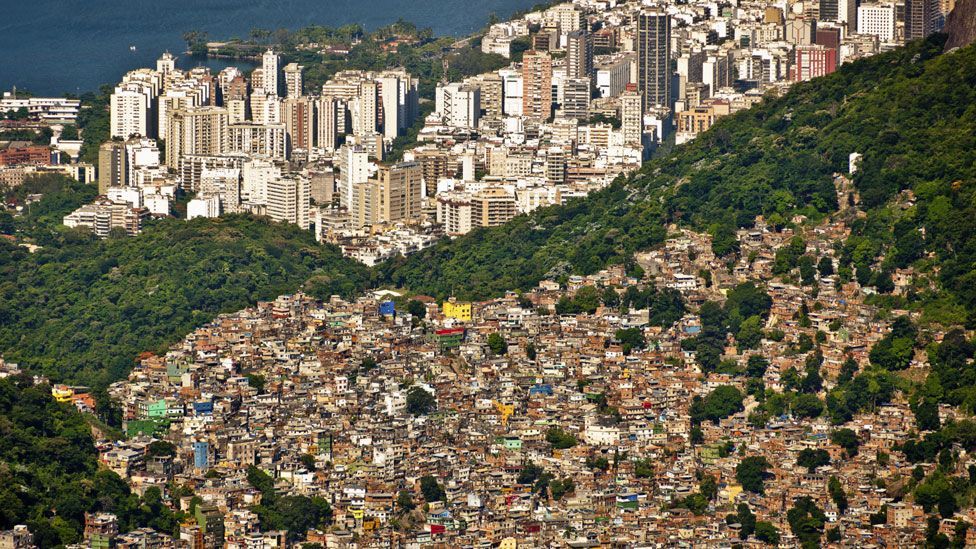

Favelas may be close to well-known cities, but they are not well-mapped (Thinkstock)

But while many communities have literally put themselves on the map, others have not. (Most likely, mapping Rio de Janeiro's favelas or the floating slum of Makoko in Lagos isn't a top priority for those living there.) Traditional paper maps tend to neglect these areas as well. "They're places that the state denies or doesn't want to portray as part of its landscape," says Alexander Kent, a senior lecturer in geography and GIS at Canterbury Christ Church University in the UK. "Far from being something objective that just reflects what's on the ground, the person behind the map has the power to determine what goes on it or not."

In recognition of this problem, a new effort called the Missing Maps Project – organised by the Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders and the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team – recruits volunteers to fill in the cartographical blanks in the developing world. It's too early to tell whether the project will make a substantial dent, but launch parties are scheduled in London and Jakarta to try and drum up interest among potential volunteers.

Coastlines often change faster than maps can track them (Getty Images)

The ocean, likewise, is one of the most poorly mapped areas of the planet, despite the fact that it occupies the most space. "The great terra incognita is the ocean bed," Brotton says. In light of increasing interest in underwater mining and drilling, certain countries – especially Russia – are looking to lay claim on large tracts of ocean floor. Additionally, with sea ice quickly receding, more and more territory will come up for grabs. "As the landscape changes, it becomes possible to exploit more mineral resources, so mapping becomes extremely powerful and important," Brotton says. To draw attention to this gap of knowledge, Brotton and artist Adam Lowe are creating a 3D map of the ocean floor without water. "I think geographers are beginning to understand that mapping the oceans is one of the great untold stories," he says.

Low quality

For others, though, untold stories abound even in some of the most prolifically mapped places in the world. Dave Imus, an award-winning mapmaker based in Oregon, acknowledges that much of the world has been mapped in a basic sense, but believes that the vast majority of maps are not good enough.

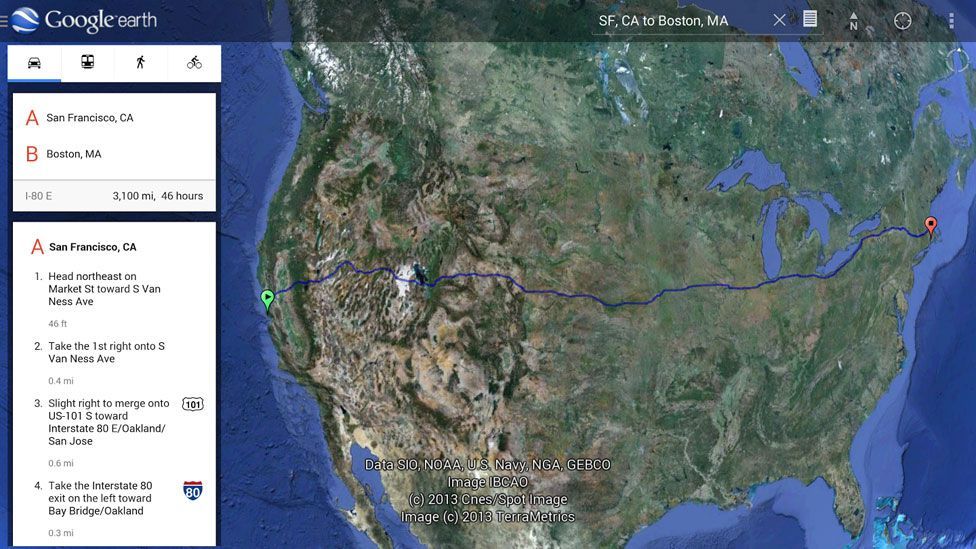

"So many maps are difficult to understand, forcing the eye and mind to work overtime trying to perceive what it's looking at," he says. And a digital map, with spoken directions, "is good for helping you find a restaurant, but you're no more connected with your surroundings than looking for the next turn".

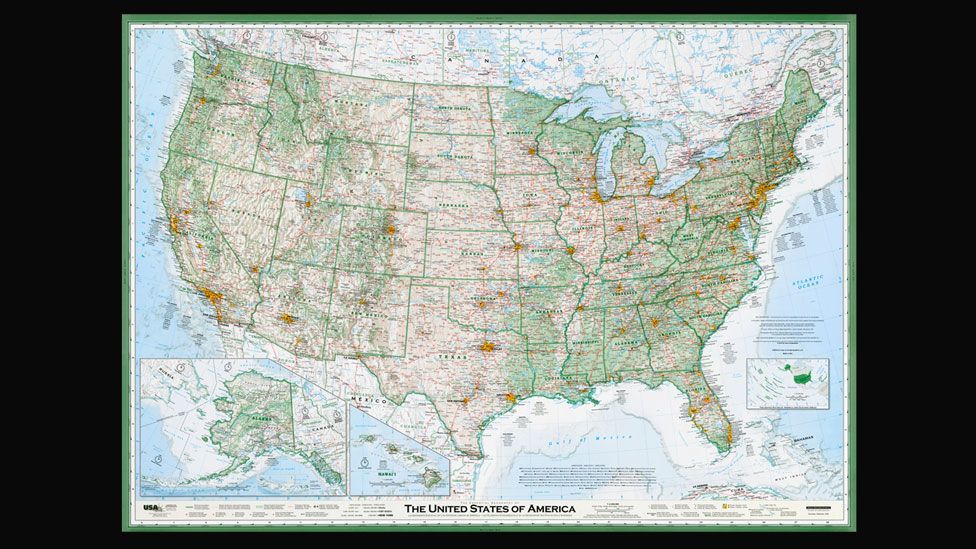

Frustrated with the maps on offer for the US, he set out to make his own, turning to the "really exquisite, expressive" mapping style of Swiss cartographers as inspiration. "It's my hypothesis that the reason Europeans are so much more geographically aware than we Americans is that they have these maps that make their surroundings understandable and we don't," he says.

The Essential Geography of the United States - for a zoomable version, visit imusgeographics.com/usa-maps (Dave Imus)

The fruit of his labour is the Essential Geography of the United States of America, a highly informative map that does away with the muddle of rainbow-coloured states of traditional US maps, instead delineating boundaries in green and allowing each state's actual features – mountains, forests, lakes, urban centres, highways – to characterise those places. City populations are indicated in yellow patches, and rather than cram in as many towns as possible, Imus uses census data to standardise rural places in terms of what counts as a hub in that particular area – whether that means 500 or 5,000 people. Major landmarks and transportation centres like airports are marked; Native American reserves are included (something lacking on many maps); and elevation of not only of mountains but also cities is noted. "The National Geographic map of the US has some elevations of mountain peaks but doesn't even tell you the elevation of Denver, Colorado," Imus says. "As a consequence, it doesn't communicate anything meaningful about what that place is like if you've never been there."

High standard

Such maps are incredibly time consuming and expensive to produce, however. Imus spent 6,000 hours on his. As a result, as far as Imus knows, only Europe, Japan, New Zealand and now the US have maps available that meet these high standards. "We think we're living in this modern age and everything's been done, but for people who look at mapping at a slightly different angle, they'll see things that still need to be done virtually everywhere," he says. Still, Imus dreams of a day when such maps will be widely available everywhere and at increasingly fine scales, such as at the state and city level. Ultimately, he hopes this would foster a more geographically literate society. "I've felt misunderstood at times," Imus says, "but I've gotten so much great feedback on this project that I feel like people now get it and it'll continue on."

Shifting climates change the shape of the land, rendering maps outdated (Getty Images)

But even the most detailed maps cannot get around one fundamental problem in the way of creating a near-perfect cartographic representation for any place in the world: the incredible pace of change, both human and nature-made, that characterises life on the planet. Some cities in Asia and Africa, Gupta says, are undergoing so much construction that Google Maps have been unable to keep up. At the same time, natural landscapes are constantly in a state of flux – now, more so than ever. Islands are being devoured by the sea, ice floes are disappearing, shorelines are eroding and forests are being cleared. "The very moment you build a perfect map of the world is the moment it goes out of date," Gupta says. "The real world will always be a little bit ahead of how we represent it, because change is constant."

In that sense, the entire world is undermapped, and it will always remain that way. A birds-eye view of a city tells you it's there, but not how to navigate through all corners of it. A foldout map is a relic of the time it went to print, unable to take into account earthquake destruction, new roads or renegotiated borders. And Google Maps can provide turn-by-turn instructions for biking from London to Brighton, but fails utterly when asked to do the same for traversing a Brazilian favela or the Gobi desert's dunes.

Even our best maps, then, are merely more up to date and truer to place than others. Our age-old quest to capture uncharted land and space will never end.

If you would like to comment on this, or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook or Google+ page, or message us on Twitter .

How to Discover Percentage Earth That I Visited

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20141127-the-last-unmapped-places

0 Response to "How to Discover Percentage Earth That I Visited"

Post a Comment